Parallel Submission to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

April 13, 2023

The Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) has submitted a parallel report for consideration by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) for the upcoming review of the People’s Republic of China at its 85th session on May 12, 2023.

The submission draws on our own research, firsthand testimonies, and additional reporting on the Uyghur crisis relating to the field of women’s rights. The report makes recommendations and suggested questions to be raised with China 85th session from May 8–26, 2023, in relation to articles 7, 11, 12, 13, and 16 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Below is our full parallel submission to the Committee.

The Uyghur Human Rights Project writes in advance of the 85th session of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women relating to the People’s Republic of China’s compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). The following submission provides suggested questions for the Committee to be raised with the government during the review, with supporting information describing specific violations.

Summary:

The government of China is perpetrating human rights abuses on a significant scale in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Uyghur region).

Hundreds of thousands of Uyghur women are subject to a program to “cleanse” them of their “extremist” thoughts through “re-education” and forced labor facilities.1The Chinese government’s terminology, see, for example, “‘Eradicating Ideological Viruses’: China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims,” Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideologicalviruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs The government is engaging in a systematic campaign to eradicate Uyghur culture, religion, and language, including destruction of sacred cultural and religious sites like mosques, cemeteries, and shrines, and detaining and imprisoning intellectuals and well-known cultural figures. China’s ban on Uyghur women wearing religious symbols is a clear, gender-specific violation of Uyghur women’s right to participation in cultural and religious life.

Forced sterilizations and coerced IUD implants for Uyghur women has been well-documented, and represents a clear violation of the Convention’s protections over a women’s bodily autonomy,2United Nations Special Procedures (October 2017). “Women’s Autonomy, Equality and Reproductive Health in International Human Rights: Between Recognition, Backlash and Regressive Trends,” Working Group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and in practice. Online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WG/WomensAutonomyEqualityReproductiveHealth.pdf as well as previous recommendations by the Committee to end the practice of forced sterilization.3Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, “Concluding observations on the combined seventh and eighth periodic reports of China,” 2014, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CEDAW%2fC%2fCHN%2fCO%2f7-8 In December 2021, an independent tribunal determined that “the PRC, by the imposition of measures to prevent births intended to destroy a significant part of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang as such, has committed genocide.”4Uyghur Tribunal Judgement (December 9, 2021) para. 190. Available online: https://uyghurtribunal.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Uyghur-TribunalJudgment-9th-Dec-21.pdf In August 2022, an assessment by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights found that these abuses “may amount to … crimes against humanity.”5Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (August 31, 2022). “OHCHR Assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China,” online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/2022-08-31/22-08-31-final-assesment.pdf

Forced sterilization (Article 12)

List of Issues (2021): “Please also provide information about non-coercive measures taken to protect and promote the sexual and reproductive health rights of Uighur women, including the right to freely decide on the number of children that they have, and about measures taken to investigate the reports of alleged coercive family planning practices in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region … Please provide information about the measures taken to abolish illegal practices such as forced abortion and forced sterilization.” (Paragraph 18)

State Party reply (2023): “China protects and safeguards the reproductive rights and interests of all ethnic groups including the Uygurs [sic] on an equal footing. The policy of family planning is implemented in Xinjiang in accordance with the law. People are free to choose safe, effective and proper contraception methods. There is no coercive family planning.” (Paragraph 59)

Suggested questions:

- Why have local governments planned mass female sterilization programs in rural Uyghur regions beginning in 2019, according to government documents?

The Chinese government response to the List of Issues report does not engage at all with the question of declining birth rates among Uyghurs. Rather, the response cites population increases among all ethnic minorities across the country, which purposefully obscures the declining birth rate among Uyghurs in particular. Likewise, the response does not respond to the allegations made by the Committee. Rather, the response simply denies the existence of coercive birth policies without refuting the specific claims based on statistical data.

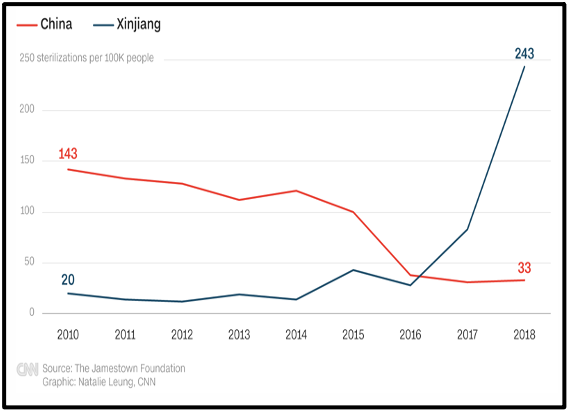

Birth rates among Uyghurs plummeted from 2015 to 2018, with population growth in the Uyghur region falling by over 84 percent in the two largest Uyghur prefectures, Kashgar and Hotan.

Since 2015, the government of China has made efforts to reduce the birthrate of Uyghur women through coercive family planning, including forced sterilization. Authorities have planned a campaign of mass female sterilization in rural Uyghur regions, noting in official documents they wish to target 14 and 34 percent of all married women of childbearing age in two Uyghur counties that year.6Ibid. The campaign aims to permanently sterilize rural minority women with three or more children, as well as some with two children, criteria which would cover at least 20 percent of all childbearing-age women. In 2018, one Uyghur prefecture publicly set a goal of leading its rural populations to accept widespread sterilization surgery.

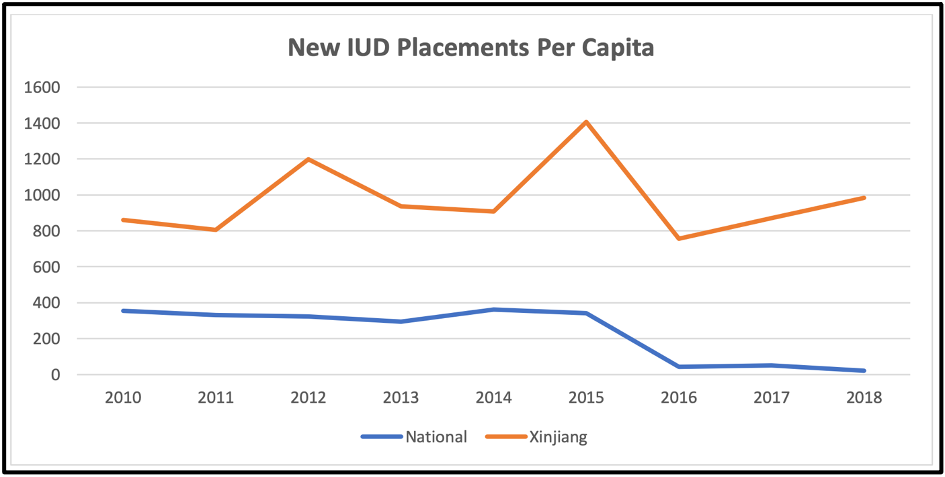

In 2018, 80 percent of all net added IUD placements in China were performed in the Uyghur region, despite the fact that the region only makes up 1.8 percent of the nation’s population. Between 2015 and 2018, the regional government placed 7.8 times more net-added IUDs per capita than the national average.

Government documents show that local authorities are instructed to punish Uyghur women who “violate” birth control targets with extrajudicial internment.7Uyghur Human Rights Project (February 18, 2020). “Ideological Transformation”: Records of Mass Detention from Qaraqash, Hotan. Available at: https://uhrp.org/report/mass-dentention-hotan/ A leaked document known as the Qaraqash List showed that in one county in the Uyghur region, the most frequently cited reason for internment of Uyghur women was a violation of birth control regulations. A Qaraqash county official, in a 2018 government work report, stated that “[by] severely curbing behaviors that violate birth control [policies], birth and natural population growth rates have declined dramatically.”8Zenz, Adrian (July 2020). “China’s Own Documents Show Potentially Genocidal Sterilization Plans in Xinjiang,” Foreign Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/01/china-documents-uighur-genocidal-sterilization-xinjiang/

Employment (Article 11)

List of Issues (2021): “Please provide information on measures taken to independently investigate reports of forced labour among Uighur women, particularly in the textile, apparel production and cotton-picking industries.” (Paragraph 16)

State Party reply (2023): “Workers of all ethnic groups in Xinjiang choose jobs on their own will, sign labor contracts with employers and receive remuneration on the principles of equality, free will and consensus, without any coercion and in accordance with laws and regulations such as the Labor Law and the Labor Contract Law.” (Paragraph 55)

Suggested questions:

- In 2023, the ILO Committee on the Application of Standards reiterated its “deep concern in respect of the serious allegations of discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang.”

There is a substantive body of evidence that the Government of China is subjecting the Uyghur population and other Turkic and Muslim-majority peoples to state imposed forced labor as part of a programme including so-called ‘poverty alleviation’, ‘vocational training’, ‘re-education through labour’ and ‘de-extremification’ focused on eliminating Uyghur culture and religious practices.

Forced labor transfers: At least 80,000 Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities have been forcibly transferred from the Uyghur region to factories in eastern and central China between 2017 and 2019. This is part of a state-sponsored transfer-of-labor scheme that goes beyond just the cotton and garment manufacturing sector, marketed as ‘Xinjiang Aid.’ The vast majority of workers forced into these “labor transfer” schemes, however, have been transferred within the Uyghur region itself—either to another prefecture or county.

Coerced labor of the rural poor in the ‘poverty alleviation programme’: The Chinese government plans to have at least one million workers in the textile and garment sectors, with at least 650,000 coming from the Uyghur region by 2023. Regional and local government directives indicate that refusal to participate in poverty alleviation in the Uyghur region is considered a sign of the “three evils”—terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism—which are punishable by internment or imprisonment.

Forced labor of current and ex-detainees, including in internment camps: In a separate but parallel policy to China’s public poverty alleviation plan, the government has enacted a public “re-education” policy that involves internment with some vocational training, indoctrination, and finally release to factories in nearby industrial parks or camp factories. Estimates based on interviews and government statements are at least 100,000 former detainees who have been forced to work in garment and textile factories.

Uyghur women are often a target of programs involving “satellite factories” within the Uyghur Region, which often amount to small workshops built in villages to put women and others with household and childcare responsibilities to work. These programs are designed to bring work opportunities to those who are unable to leave the village to take up non-rural or non-farming jobs, often targeting women responsible for caring for children and elderly family members. Government documents indicate that these programs are designed with ‘thought transformation’ in mind to convince women to participate, and some documents arguing that the satellite factories liberate women and combat extremism at the same time, leading Uyghur women into an acceptance of “modern culture.”

In one case of labour transfers outside the Uyghur Region, a group of around 600—mostly Uyghur women from Hotan and Kashgar prefectures—were transferred to Qingdao Taekwang Shoes Co. Ltd, a shoe factory located in Laixi City on the north east coast of China. Uyghurs working at the factory were compelled to take “night classes” where they study Mandarin, sing the Chinese national anthem and receive “vocational training” and “patriotic education,” and were not allowed to go home for holidays.

Forced Marriage (Article 16)

List of Issues (2021): “Please inform the Committee about specific action taken to adopt a comprehensive definition of discrimination against women in national legislation in order to protect women, in particular ethnic minority (Uighur) women, from both direct and indirect discrimination, in line with article 1 of the Convention.” (Paragraph 2)

State Party reply (2023): “The Civil Code makes provisions to eliminate discrimination against women, protect women’s freedom of marriage and achieve gender equality, on issues such as the minimum legal age for marriage…” (Paragraph 7)

Suggested questions:

- Why are local governments in the Uyghur region permitted to offer financial incentives for interethnic marriages? And how does this practice comply with the Convention’s guarantees that to freely choose a spouse and to enter into marriage only with free and full consent?

According to recent research, it is highly likely that the Chinese government is systematically imposing forced interethnic marriages on Uyghur women.9Uyghur Human Rights Project (November 2022). “Forced Marriage of Uyghur Women: State Policies for Interethnic Marriages in East Turkistan,” Retrieved from: https://uhrp.org/report/forced-marriage-of-uyghur-women/ Chinese state media videos, government sanctioned stories, and accounts from women in the diaspora offer evidence that government incentivized and forced interethnic marriages have been occurring in the Uyghur region since 2014.

The Chinese state maintains that interethnic marriage promotes ethnic unity and social stability. However, evidence indicates that the government’s program to incentivize and promote interethnic marriage is in fact a tactic intended to assimilate Uyghurs into Han society. Forced and incentivized marriages in the Uyghur region are forms of gender-based crimes that violate international human rights standards and further the ongoing genocide and crimes against humanity being committed in the Uyghur region.

Right to participation in public and cultural life (Articles 7 and 13)

List of Issues (2021):“Please inform the Committee about specific action taken to adopt a comprehensive definition of discrimination against women in national legislation in order to protect women, in particular ethnic minority (Uighur) women, from both direct and indirect discrimination, in line with article 1 of the Convention.” (Paragraph 2)

State Party reply (2023): “It is a fundamental principle enshrined in the China’s Constitution and other laws that everyone is equal before the law and discrimination against women is strictly prohibited.” (Paragraph 7)

Suggested questions:

- How will the Chinese government ensure Uyghur women have the ability to participate in religious and cultural life?

- Will the Chinese government stop the detention of Uyghur women for religious teaching?

The government of China has detained and sentenced well-known female intellectual and cultural figures including professors, editors, researchers, teachers, and government officials.10Uyghur Human Rights Project (December 2021). “The Disappearance of Uyghur Intellectual and Cultural Elites: A New Form of Eliticide,” online: https://uhrp.org/report/the-disappearance-of-uyghur-intellectual-and-cultural-elites-a-new-form-of-eliticide/

Rahile Dawut, a prominent Uyghur scholar and leading expert on Uyghur folklore and traditions, taught at Xinjiang University up until 2017 and her work had been sponsored and supported by the Chinese government. Rahile disappeared in December 2017 and was not heard from publicly until it was confirmed in July 2021 that she is serving a prison term.11Radio Free Asia (July 21, 2021). “Noted Uyghur Folklore Professor Serving Prison Term in China’s Xinjiang,” online: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/rahile-dawut-07132021175559.html

Gulnisa Imin, a Uyghur literature teacher and poet, was detained in December 2017, reportedly for her ideas about preserving and promoting the Uyghur language and culture. Imin’s poetry has garnered wide acclaim online where many Uyghur authors have long self-published poetry as a means of circumventing exclusionary publishing practices. On December 6, 2021, it was reported that Gulnisa has been sentenced to 17 years, 6 months’ imprisonment on still-unknown charges.

The government of China’s restrictions on Uyghur cultural and religious expression also extend to women who take up leadership roles in local religious affairs and teaching, particularly Uyghur women who serve as büwi—a religious role which includes various duties in the community. In recent years, the Chinese government has attempted to expand its oversight and control of Uyghur women serving as büwi.12Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom,” p. 29, https://docs.uyghuramerican.org/Sacred-Right-Defiled-Chinas-Iron-Fisted-Repression-of-Uyghur-Religious-Freedom.pdf

Uyghur women have also been banned from wearing long skirts or burqas as part of a campaign to assimilate Uyghur women into Han-Chinese culture.13Dearden, Lizzie, “China bans burqas and ‘abnormal’ beards in Muslim province,” The Independent, March 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/china-burqa-abnormal-beards-ban-muslim-province-xinjiang-veils-province-extremism-crackdown-freedom-a7657826.html Police have stopped Uyghur women in the street to forcibly “cut down” the length of their traditional skirts.14Chan, Tara, “Police are reportedly cutting too-long dresses off ethnic minority women in the middle of streets in China,” Business Insider, July 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/police-cutting-dresses-off-uighur-women-in-xinjiang-china-2018-7?r=US&IR=T In addition to “religious clothing” bans, the Chinese government has deployed state media to ensure Uyghur women do not dress in a way that expresses their Uyghur identity. In 2011, government officials launched “Project Beauty,” a five-year multimedia propaganda initiative encouraging Uyghur women “to shun the niqab and jilbab” in lieu of modern fashion. Since then, fashion shows and beauty pageants have aimed to encourage “Chinese modern fashion” with the public goal of “transforming” Uyghur women’s way of life.15Palash, Ghost, “Project Beauty: Chinese Officials Pressure Uighur Muslim Women In Xinjiang To Drop Their Veils, Men To Cut Beards,” IBTimes, November 2013, https://www.ibtimes.com/project-beauty-chinese-officials-pressure-uighur-muslim-women-xinjiang-drop-their-1487184

In order to implement the numerous municipal bans on head-scarf wearing, officials have repeatedly harassed and restricted the rights of headscarf-wearing Uyghur women.16Grose, Timothy, “Why China Is Banning Islamic Veils,” ChinaFile, February 2015, https://www.chinafile.com/reporting-opinion/viewpoint/why-china-banning-islamic-veils In 2014, officials in the cities of Qaramay and Ghulja banned Uyghur women from entering public spaces, government offices, and public buses if they were wearing face veils, jilbab, hijab, or a piece of “star-and-crescent” themed clothing.17Henochowitz, Anne, “Minitrue: No Beards on Xinjiang busses,” China Digital Times, August 2014, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2014/08/minitrue-beards-xinjiang-